Foreigners in Japan can and do get away with all sorts of things that Japanese people would never dream of. (This is the flip side of being a gaijin — literally, an "outside person".) Taking advantage of this fact is commonly called "playing the gaijin card".

Playing the gaijin card usually involves feigning ignorance of local rules, like skiing off-piste because you “couldn’t read the sign” saying not to. Most Japanese people won’t try to correct a foreigner who is out of line, either because they assume he can’t speak Japanese, because they don’t feel comfortable speaking English, or just because they don’t want to get involved in a confrontational situation.

Even when caught red handed, gaijin are frequently let off the hook. For example, a cop may just warn a foreigner to slow down instead of going through the whole ticket-writing procedure.

But gaijin-ness doesn't always push Japanese people away; often, it draws them closer. For example, many foreign guys in Japan are pleasantly surprised to find themselves much more popular with the ladies here than they ever were at home. It's not because they suddenly became better-looking when they stepped off the plane; it's because in Japan they're exotic, they're different, and they follow a different set of rules. (If there's one thing women like, it's a man who plays by his own rules.)

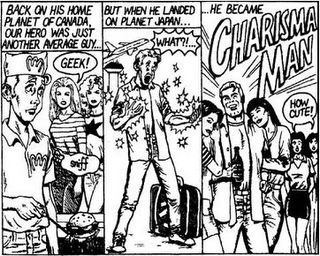

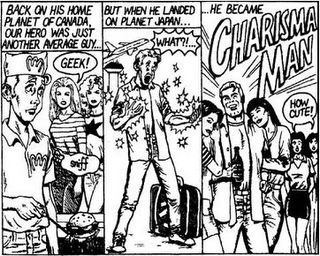

This phenomenon was infamously parodied in the comic strip Charisma Man, which debuted several years ago in an English-language Tokyo magazine:

|

My own personal experience (before I met my lovely girlfriend, of course — hi, honey!) suggests that the above depiction is not all that much of an exaggeration. But the benefits of being a gaijin aren't limited to getting better customer service and feeling like Austin Powers in the 60's. They also include getting to run major multinational corporations.

In June 2001,

Carlos Ghosn, a Frenchman born in Brazil and raised in Lebanon, was named CEO of Nissan, the Japanese carmaker. Nissan was losing money hand over fist, but none of its Japanese executives felt comforable taking the drastic steps that would be necessary to effect a recovery. Free of Japanese cultural obligations, Ghosn was able to slash costs, cut jobs, and reorganize the company; Nissan has posted a net profit every year since he took the job.

Sony, which has

fallen on hard times of late despite the success of its videogame unit, is looking to try the same approach. The company recently replaced former CEO Nobuyuki Idei with Harold Stringer, an American originally from Britain, who previously ran Sony's U.S. entertainment division. And he's clearly expected to shake things up. As CNN

reports:

Analyst Flint Pulskamp of research firm IDC said Sony, which earlier this month promoted U.S. operations chief Howard Stringer to the top corporate spot, is most likely to expand outsourcing to the large companies with which it already does business.

Piper Jaffray analyst Jesse Pichel said Sony's cost of producing each gizmo — $14.5 billion in its latest quarter — represents the company's potential market for outsourcing.

Pichel said the Japanese have generally been reluctant to outsource because of the cultural norms there for lifetime employment.

But analysts said Stringer, a Welsh-born former television journalist, will find it easier to make big shake-ups at Sony than a native Japanese CEO would.

"Stringer doesn't have a lot of the baggage or the cultural inhibitions that a Nobuyuki Idei did," Pulskamp said, referring to Sony's former chief executive.

So, is Japan doomed to become a nation of companies led by foreigners? History suggests the answer is no.

Japan has a long tradition of first borrowing technology from overseas, studying it carefully, and then developing a made-in-Japan version. Its first cars were imported from overseas; next (as David Halberstam describes in his excellent book

The Reckoning) came a process of importing car makers themselves, like

William R. Gorham, who

developed many of Nissan’s

earliest car models, and quality-control experts like

W. Edwards Deming, who helped Japanese companies dramatically improve production. Soon, companies like Nissan, Toyota, and Honda were turning out excellent cars on their own, and quickly leapt to the front of the global automotive industry.

My hunch is that executives like Ghosn and Stringer represent the early stages of a transformation of Japanese management, in much the same way that Gorham and Deming kicked off a transformation of Japanese production. Japanese businessmen may not like making aggressive, confrontational moves yet, but they'll learn to soon enough.

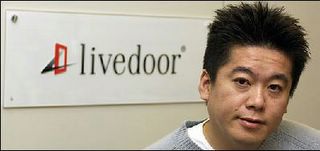

Some of them already have. Consider Japan's youngest Internet mogul, Takafumi Horie:

About eight years ago, while still a student at Tokyo University, Horie formed a web design company with the unconventional name of Livin' on the Edge Ltd. At the time, he was just 23 and his company had about $45,000 in capital. After Horie dropped out of Tokyo U., Bill Gates-style, he grew his company, largely by acquisitions, into a diverse IT, networking, and e-commerce firm with a market capitalization of over $2 billion. It's currently known as

Livedoor, taking its name from an ISP it acquired back in 2002.

Horie, now all of 32 years old, has been a fixture on Japanese news shows for the better part of a year, since he tried (and failed) to buy a professional baseball team, the Kintetsu Buffaloes, last summer. But more recently, he's been in the news for a different reason: trying to gain control of Fuji Television, one of Japan's largest media companies.

On February 8, Livedoor bought almost 30% of the shares in Nippon Broadcasting System (NBS), bringing its total stake to 35%. As the biggest shareholder in NBS — which was itself the biggest shareholder in Fuji TV — Livedoor would have be able to influence managerial decisions at Fuji.

While similar takeover bids have been par for the course in the U.S. for decades, they're unusual in Japan, where companies have traditionally held each other's shares in cozy, stable "cross-shareholding" relationships designed to prevent outsiders from buying a controlling stake. Even more interesting than the rarity of the takeover attempt itself, though, has been Japan's reaction to it.

In America, hostile takeovers, and the dealmakers behind them, are seen as essential tools for weeding out inefficient management and making sure corporate assets are put to their most effective use. The Japanese financial and media establishment's reaction to Horie's NBS bid, by contrast, ranged from dissaproving to downright hostile.

In a news article that seemed an awful lot like an editorial, the

Asahi Shimbun complained that Livedoor used "clever financial magic tricks" to finance the NBS share purchase:

So with a market capitalization that has grown threefold over the past 14 months or so to 300 billion yen, Livedoor convinced a foreign securities group to underwrite the convertible bonds and lend it the 80 billion yen needed to buy the Nippon Broadcasting shares.

Presto — a rabbit from the hat.

Fujio Mitarai, the president of Canon,

blasted Horie for buying the NBS shares in (perfectly legal) off-hours trading, instead of revealing his plans by publicly announcing a tender offer:

Off-hours trading is legal and has some merits, but restrictions should exist on such stock trading. Social ethics and manners are required for corporate mergers and acquisitions.

And speaking at a press conference, Hiroshi Okuda, head of the powerful Japan Business Federation (

Keidanren)

attacked Horie simply for having the gall to go after a larger company:

He has been criticized by people in political and business circles for having done something morally wrong, because it is the worst thing in Japanese society to think that if you have money, you can do anything. Mr. Horie should humbly accept the criticism.

After a complex series of developments, culminating in NBS lending its Fuji shares to another company to keep them out of Livedoor's hands, it now appears Horie has ultimately

failed in his effort to gain control of Fuji. But while he may have lost this particular battle, and is being savaged by the old business elite, he appears to be winning the war of public opinion among younger Japanese. As the

Mainichi Daily News reported:

Horie has often appeared without a necktie, and his enterprising approach has drawn criticism in Japan's corporate circles. But he has also found supporters among the young generation.

"It's great to see him appearing on TV programs full of confidence," said Miki Hirano, a 20-year-old university student in Kyoto. "I much prefer Livedoor, a young and ambitious company, to Fuji TV."

Ruriko Kunitake, 39, a company worker from Yame, Kumamoto Prefecture, said she found a reformer in Horie. "Every industry needs replacements. I admire Horie because he stands up under pressure."

If Horie's ambitious attempt to shake up a major Japanese company is any indication, Japan's future cost-cutting turnaround specialists won't come from France or America; they'll come from Japan itself.

Long ago, Japan learned how to make its own cars. Now it's learning how to to make its own gaijin.

» Read More...